Birds & Bones

2012, Gallery 916 (Tokyo) /

「Birds & Bones」 Gallery 916 (東京)

Overview

Date : March 25 – July 10, 2012

Open : Weekday 11:00 – 20:00

Weekends and Holidays 11:00 – 18:30

Closed Mondays

Venue : Gallery 916

6F No.3 SUZUE Bldg.1-14-24 Kaigan , Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Contact Us : tel +81-(3)-5403-9161/fax +81-(3)-5403-9162

mail[a]gallery916.com

Admission : Free

http://gallery916.com

Photos that cleanse the soul

Toshiharu Ito (art historian)

Birds fall from the sky, land on the ground and lie shrouded in darkness, in poses suggesting they have only just this moment met their demise.

Or, are they in fact still alive, barely – frozen in some semi-dead state, ever on the brink of revival?

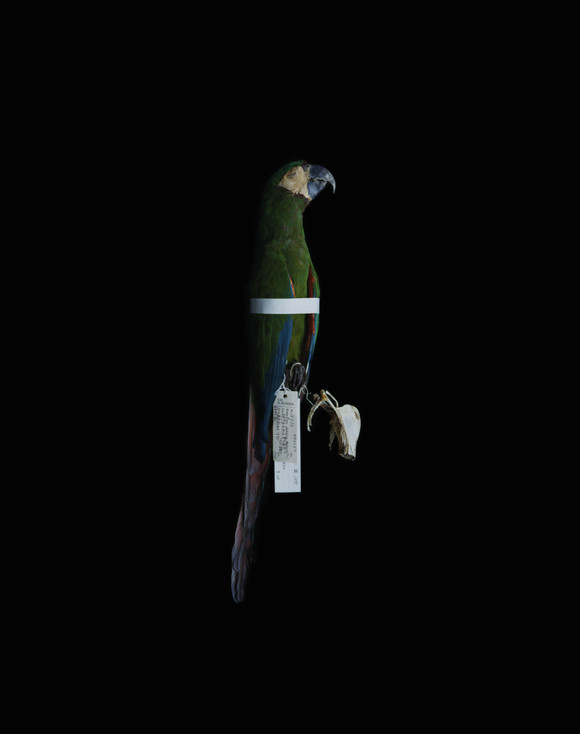

A Papuan hornbill curled fetus-like; a purple-crested turaco proudly displaying its noble crown-like head; an Amami jay with its resplendent, translucent azure sheen; a quetzal whose special feather structure allows it to swiftly alter the color and luster of its plumage; a chestnut-fronted macaw concealing feathers of a vibrant moss green… all hover in the gap between life and death, as if dozing. Then there are the skulls of creatures such as deer and elephants echoing of vanitas or memento mori; and huge, filled eggs serving as cosmic eggs, perhaps, or incubators.

Studying Yoshihiko Ueda’s photographs of these birds and bones lying in pitch blackness, cloaked in sacred moisture, with hints of life that suggest movement at any moment, one feels a surreptitious thrill of the unknown. Ueda seems to be trying to catch the last breaths and fading pulses of the birds. His photos restore them from death to a kind of asphyxia, a semi-dead state, thus making death segue into the foundations of life. As if to witness the moments of the birds’ deaths, Ueda attempts to summon up in images the latent power of the space between life and death, inherent in death’s instant.

By hiding their breathing and adopting fixed stares for so long amid singular silence, these birds endow their tiny deaths with a whiff of life. Harboring powerful impulses toward destruction and decay, confined in an invisible, unstable structure, they remained astoundingly graceful, right down to the most intricate detail. There is something strangely alluring in gazing on their shimmering, pulsing deaths. They have been captured on film out of the photographer’s urge to understand what such a death might be. Can bestowing dignity on that which was alive and on its death, endowing the form of that death with meaning; can a gaze that takes in life and death simultaneously, a gaze that views death as the foundation of life, be described as a natural history-oriented gaze? Natural history is a composite realm of images that seeks to compile all knowledge of the natural universe and identify within it common points and heterogeneities, and a place of questing that bears the swollen current of the history of the natural world.

Thinking about it, the act of perceiving beauty is deeply entwined with the generation of forms in nature. We find things beautiful because our own minds and bodies, also part of nature’s generative process, resonate mutually with the external generative processes of nature. French anthropologist and archeologist André Leroi-Gourhan once turned his attention to a cluster of unusual objects found in the remains of a dwelling inhabited 50,000 years ago: a collection of mysterious items from nature assembled by our paleolithic ancestors and including a lump of pyrite with various protrusions, the shell of a fossilized gastropod, a cluster of spherical polyps from the Mesozoic era, fragments of bird and cattle bone, tusks, and teeth. Thus these ancient humans brought home forms of special note from the natural world, the realm of life, and groups of objects created by the power of nature; and proceeded to study, handle, and cherish them. As well as being emblems of the forms and movement of nature, they resembled ideas and words spun by nature over an extraordinary length of time. Evidently our ancestors perceived relics of such a variety of shapes, colors and textures as wonders, and attempted to find special significance in them as objects linked directly to their own profound memories. No doubt they intuitively felt such things to be connected to the very origins of life.

Human beings continued to search for objects created by the concentration of nature’s infinite powers over eons, and in order to engage with such objects as an essential experience, endeavored to collect and appreciate them. Human beings harbor deep within them emotions directed toward the inherent sacredness and mystery of such strange forms; this “nest of emotions” acting as the wellspring of human imagination and behavior. And through the diversity of human experience, such symbols of the intersection of nature and human emotion were passed down as examples of living beauty, eventually spawning the format that would become the prototype for collecting, and the cabinet of curiosities. In other words, en route from medieval to modern, a conscious enjoyment of unusual forms in nature led to a fashion for collecting, and based on such collections the likes of natural magic, alchemy, and astrology made their appearance, followed by genres such as medicine, chemistry, pharmacology and biology, which took the knowledge systems of these earlier arts to even more specialized heights. Meanwhile, the format of the museum, legacy of the cabinet of curiosities, developed in leaps and bounds alongside progress in preservation technologies as a setting for the collection of special and unusual objects.

The bird specimens photographed by Yoshihiko Ueda were carefully chosen from one of the world’s largest avian collections, numbering an incredible 70,000 specimens, at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, inheritor of the aforementioned collections and cabinets of curiosities. These are more than just specimens of birds. The birds looming in vivid contrast out of the blackness have been clothed in garments and gauze possessing an elegant, sacred quality. The figures of the specimens themselves are of course graceful, even sensuous, but the glass cases, the shelves, the drawers, the little boxes, washi paper, labels with the name of the maker, cords binding legs, bandages, white cotton sheets and red tags all used in their containment…all these garments and gauzes exemplify a neat, refined aesthetic. Moreover, various ingenious means have been found with these specimens to swing death back to life, and life to death. In particular, these birds are not complete examples of the taxidermist’s art, but have merely been partly stuffed by removing the decay-prone entrails and bones of the torso, and inserting cotton in place of the eyeballs before filing on shelves with their wings folded and wrapped in bandages. That the birds have not lost their plump freshness or suppleness is due to this method of partial taxidermy. Ueda captures with infinite precision this immediate post-mortem ambience or quality, and it with this precision that death slowly shimmers back into life, and life to death.

Once again, our perception of beauty is connected to the accumulated memories of human and nature. Individual feelings of beauty are not those of the individual, but linked to those passed down over generations from the experiences of countless individuals. One might venture that our perceiving of beauty is the transmission of noise from the memories of countless people lying within each of us. Aesthetic perception is the recrystallizing in the individual of a great current of memory, an action woven into nature’s generative processes.

If this is the case, it means the taker of the photo must be closely connected to the condition of the taken. Things that have lost their lives can only become beautiful through the instinctive understanding and lifelike perception of something possessing life. The photos of Yoshihiko Ueda are predicated on this relationship, purifying death and life, and silently restoring to life that which has lost it. This power to change death to life and life to death is precisely what underpins the gaze of natural history. Scientific observation and artistic insight form a well-rounded whole, a gaze in which profound experience induced by the working of each on the other gives rise to translucent, purified imagery.

One may study the forms of nature in intimate detail, and find that as one watches, the shapes of things change. As one continues to watch, their structure and fibers begin to unravel. There is nothing immutable in this world, nor anything not connected to something else. All is in a state of constant transformation. That forms become fixed amid this swirling flux is due to a rigorous mechanical interplay between materials and space, the story of this process told by the forms themselves.

The forms of nature may, for all we know, emerge from just a single set of plans. A natural history-oriented gaze is none other than the intuitive grasp of that invisible design. Over a long period, in the process of photographing people and forests, animals and minerals, bones and flowers, vessels, landscapes and more, Yoshihiko Ueda has honed that gaze, every fiber of his being becoming alert to it. “Birds and Bones” is the stunning outcome of this rare perspective, and no doubt from it we will continue to hear, like distant birdsong, the exquisite teachings of the natural world brought to us through the camera’s enquiries, messages from that invisible network to which we ourselves are connected.

開催概要

会期 : 2012年5月25日 – 7月10日

開館時間 : 平日 11:00 – 20:00

土、日、祝日 11:00 – 18:00

休館日 : 月曜日

会場 : Gallery 916

東京都港区海岸1-14-24 鈴江第3ビル 6F

お問い合わせ : tel 03-5403-9161 / fax 03-5403-9162

mail[a]gallery916.com

入場 : 無料

http://gallery916.com

浄める写真

伊藤俊治(美術史家)

鳥たちは空から落下し、地に堕ち、死の直後のような佇まいを見せ、闇に横たわる。

いや、まだ微かに生きていて、仮死状態に留まっているのだろうか。

胎児のように身をくるんだパプアシワコブサイチョウ、高貴な冠のような頭部を誇らしげに掲げるスグロエボシドリ、瑠璃色の透明な質感を纏うルリカケス、特殊な微細構造により色彩と光沢を次々と変えるカザリキヌバネドリ、苔のように鮮やかな色素を秘めたヒメコンゴウインコ…鳥たちは微睡むように生と死のあわいを漂う。そして“ヴァニタス(儚さを知れ)“や“メメントモリ(死を想え)”としての鹿や象の頭蓋骨と、“宇宙卵“や“孵化器“としての巨大な重填された卵。

漆黒のなかで聖なる湿気を帯び、今にも動きだしそうな生気を秘めた鳥と骨、上田義彦が撮影したそれらの写真を見ていると何か見知らぬ密やかな感覚がざわめく。上田は鳥たちの最後の呼吸や消え入ろうとする鼓動を聞き取ろうとしているかのようだ。写真が死を仮死状態に戻し、写真が死を生の基盤のものへ滑り込ませる。上田は鳥たちの死の瞬間に立ち会うかのように、その死の瞬間が内包する、死と生のあわいが秘める潜在的な力をイメージとして呼び覚まそうとする。

長い時間、途方もない沈黙のなか、息を潜め、じっと凝視することで鳥たちの小さな死は微かな生を帯びる。崩壊と腐敗へ向かう強い衝動を抱えたまま、不可視の不安定な構造に留められた鳥たちは、目の覚めるような優美さを細部に渡り保持していた。その揺動する死を凝視することには深い魅惑がある。そのような死とは何なのかを理解したいという思いとともに撮影する。生きていたものとその死に尊厳を与え、その死の形式に意味を与えること、そうした生と死を同時に見つめる眼差し、死を生の基盤とみなす眼差しを博物学的眼差しと言うことができるだろうか。博物学とは「natural history」の訳語だが、それは自然宇宙の知識を集大成し、その共通項と異質性を見極めようとする総合的なイメージ世界であり、自然の歴史の厖大な流れを背負う探求の場である。

考えてみれば美を知覚するということは自然の形態の生成に深く関わっている。私たちが美しいと感じるのは自然の生成プロセスである自らの心身と外部の自然の生成プロセスとが共振しあうからである。かつてフランスの人類史学者・考古学者アンドレ・ルロア=グーランは五万年前の人間の住居跡に残された奇妙なオブジェ群に注目したことがある。それらは様々な突起を持つ黄鉄鉱の塊、化石化した腹足類の貝殻、中世代の球状ポリプ群体、鳥や牛の骨片、牙、歯など旧人により収集された不思議な自然物だった。旧人たちは自然界や生命界の際立った特質を持つ形態群、自然の力の働きかけにより生み出されたオブジェ群を住居に持ち帰り、見入り、触り、愛でた。それらは自然の形態や運動の表象であるとともに自然が途方もない時間をかけて紡ぎ出してきた思想や言葉のようなものだった。多様な形態と色彩と質感を秘めた遺物を彼らは明らかに不思議なものと認識し、自分の深い記憶と直結するものとして特別な意味を見いだそうとした。おそらくそれらが生命の根源的なものと結びついていると直感したのだろう。

自然が無数の力を凝集させ、長い時間をかけてつくりだしてきたオブジェを人間は探し求め続け、そのようなものに触れることを欠けがえのない体験として留めるために、それらを収集し、鑑賞しようとした。そうした奇妙な形態が内包する聖性や神秘へ向かう感情が人間の奥深くに宿り、人の想像力や行動はその“感情の巣”をもとに生まれていった。そしてそうした自然と人間の感情の交差の印はその後も人間の多様な体験を通じ、生きた美として受け渡され、やがてコレクション(収集)やキャビネ・ド・キュリオシテ(珍奇陳列室)の原型となる形式を生み出してゆく。つまり中世から近代へ至る道筋のなかで珍しい自然の形態美を享受するという意識からコレクションの流れが派生し、そのコレクションを基に自然魔術や錬金術や占星術が現れ、さらにそれらの知の体系を特化させた医学、化学、薬学、生物学といったジャンルが出来上がっていったのだ。他方、キャビネ・ド・キュリオシテを受け継いだミュージアムという形式が特別なものや奇妙なものを収集する場として、保存テクノロジーの進展とともに大きな展開を遂げてゆく。

上田義彦が撮影した鳥の標本は、そのようなコレクションとキャビネ・ド・キュリオシテの流れを汲む山階鳥類研究所の七万点にも及ぶ世界最大級の鳥類コレクションから厳選されたものである。それらはただの鳥の標本ではない。闇のなから鮮明に浮かび上がってくる鳥たちは典雅で神聖な衣と紗を施されている。標本そのものの姿態ももちろん優美で官能的でさえあるが、その標本を納める硝子箱や棚、抽斗、小函、和紙、作成者の名を付されたラベル、脚を括る紐、体を巻く封帯や白綿、赤いタグ…そうした衣と紗のすべてが端正で洗練された美的感覚に満たされている。しかも標本には死を生に、生を死に揺り戻すための様々な工夫が凝らされる。特にこの写真の鳥たちは本剥製ではなく、腐敗しやすい内臓や駆幹部の骨を取り出し、眼球の代わりに綿を詰めただけの仮剥製の方法で、翼を折り畳み、封帯を巻いた状態で棚に収蔵され、保存されていたものだ。鳥たちの姿態から瑞々しさやしなやかさが失われていないのはこの仮剥製という方法のためである。上田はそのような死の直後のような気配や特性を限りなく厳密に定位させる。その厳密さゆえに死は生に、生は死にゆっくり揺り戻されてゆく。

繰り返すが、美の知覚は人間と自然の記憶の集積と関係を持つ。個の美の感情は個のものではない。それは何世代にも渡る多くの人々の体験から受け継がれてきたものと繋がっている。美の知覚とは個が潜在させている無数の人間の記憶のざわめきの伝達と言ってもいいかもしれない。美の知覚とは厖大な記憶の流れの個における再結晶作用であり、その作用は自然の生成プロセスに織り込まれている。

そうした視点に立つなら写すものは写されるものの有り様と深く関与することになる。生命を失ったものの美しさは生命あるものの本能的な理解と生命的な知覚によってのみ美しいものになりうる。上田義彦の写真はまさにそうした関係の上に成立し、死と生を浄め、生命を失ったものを寡黙に甦らせる。そしてそのような死を生に、生を死に変える力こそが博物学的眼差しの根底にあるものだ。科学的な観察と芸術的な洞察が渾然となり、両者の相互作用により深い体験が導き出されるような眼差しが透きとおった、清められたイメージを生み出す。

自然の形態を精密に凝視する。見つめてゆくうちに物の姿が変わってゆく。見つめ続けると物の組織や繊維が解かれてゆく。この世界に変化しないものは存在せず、他と繋がりを持たないものもない。すべてのものは絶え間なく変容している。そのような変容の渦のなかである形態が定まるということは物質と空間の間に何らかの力学的な相互作用が緊密におこなわれているためであり、そうしたプロセスは形態そのものが物語として伝えてくる。

自然の形態はもしかしたらたった一つの設計図をもとに生まれているのかもしれない。博物学的眼差しとはその見えない設計図を直感することに他ならない。上田義彦は長い間、人間や森、鉱物や動物、骨や花、器物や風景などを撮影するプロセスのなかで、こうした博物学的眼差しを研ぎ澄まさせ、自己の神経の隅々に張り巡らしてきた。「Birds & Bones」はその類い希な眼差しの麗しい成果であり、私たちはそこからカメラによる探究がもたらす自然の精妙な教えを、私たち自身が結びつけられている見えないネットワークからのメッセージを遠い啼き声のように聞き続けることができるだろう。